continuing education

Part I: Healthy Sight Counseling and Diabetes

An overview of diabetes and the eye for the eyecare professional

The goal of Healthy Sight Counseling (HSC) is to provide eyecare professionals with a blueprint to promote Healthy Sight in patients. Healthy Sight (HS) may be defined as the enhancement of both the quantity and the quality of vision and the protection and preservation of good sight through maintenance and preventive eyecare. HSC aims to erase the artificial distinction between vision care and eyecare and to recognize and build upon the important relationship between ocular and systemic health. There are few conditions where the principles of Healthy Sight Counseling can be more meaningfully applied than in diabetes mellitus. Diabetes in the context of Healthy Sight Counseling will be discussed in two parts. Part I, in this issue, will cover basic aspects of diabetes and diabetic eye disease. Part II, which will appear in a subsequent issue, will concentrate on special risk groups for diabetes.

Diabetes mellitus is fast becoming the leading public health concern of this 21st century. Its prevalence is reaching near-epidemic proportions, with nearly 300 million diabetics worldwide at this time. The U.S. has been especially hard hit. Currently there are an estimated 20.8 million Americans with diabetes, representing seven percent of the population. While these numbers are impressive in themselves, what is more alarming is the comparison with statistics from a decade ago: In 1996, only 8.5 million Americans, or 3.2 percent of the population, had diabetes. Diabetes is on the rise, as is diabetes-related eye disease, which is now the principal cause of all new cases of blindness in the U.S. among individuals 20 to 74 years old.

DIABETES & THE EYECARE PROFESSIONAL

While the diagnosis and management of diabetes falls primarily under the province of the internist, pediatrician, or endocrinologist, the intimate relationship between the systemic disease diabetes and the ocular disease diabetes suggests the need for a true partnership between health care professionals and the eyecare professional in dealing with diabetic patients.

Diabetes-related ocular disease is one of the most feared complications of diabetes, and it contributes significantly to the overall morbidity associated with this disease. Visual impairment occurs in 23.5 percent of diabetics over age 50; this is nearly twice the figure for non-diabetics in the same age group (12.4 percent). Diabetic complications, both ocular and systemic, increase with the duration of disease and its severity. After 20 years, 40 percent of all diabetics will demonstrate some degree of diabetic retinopathy; in 20 percent it will be vision-threatening.

Unfortunately for many individuals with diabetes, it may be a silent disease in its early stages, and the delay in diagnosis and in the institution of appropriate therapy can produce serious complications before it is even recognized.

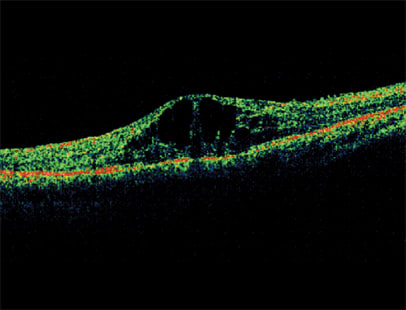

OCT showing diabetic macular edema (DME)

There are more than six million Americans with diabetes who are currently undiagnosed. Of more concern to the eyecare professional is the finding that 20 percent of all newly diagnosed diabetics display some form of diabetic retinopathy at the time when their disease is first recognized, so that ocular complications may sometimes be the presenting finding in the diabetic.

DIABETES: THE SYSTEMIC DISEASE

Diabetes is a metabolic disorder characterized by hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, hyper- or hypo-insulinemia, and progressive pancreatic B-cell failure. There are two types of diabetes: Type 1 and Type 2. Nearly 90 percent of all diabetics are Type 2.

Type 1 diabetes is caused by a decrease in or an absence of insulin production. Genetic, autoimmune, toxic, and infectious mechanisms have been implicated in its etiology. The therapy of Type 1 diabetes centers on insulin replacement. With Type 2 diabetes, the problem lies with insulin resistance and a relative deficiency of insulin, resulting in chronic hyperglycemia. It is Type 2 diabetes that is primarily responsible for the current increase in the incidence of diabetes worldwide. Important risk factors for Type 2 diabetes are overeating (especially carbohydrates), obesity, and a sedentary lifestyle.

Therapy for Type 2 diabetes includes weight loss, dietary restriction, increased activity and exercise, and a growing list of medications that reduce insulin resistance, address insulin deficiency, or delay the intestinal absorption of carbohydrates.

There exist two misconceptions about the two types of diabetes. First, many people consider Type 1 as the "bad" diabetes and regard Type 2 as being relatively innocuous. When it comes to the ocular complications of diabetes, this is simply not true. While it usually takes longer for diabetic retinopathy (DR)—the most important ocular complication of diabetes—to develop in individuals with Type 2, it is seen in both types of diabetes.

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR), the most severe form of DR, occurs in about 25 percent of Type 1 diabetics after 15 years of disease, compared to 25 percent of Type 2 diabetics after 25 years. Even the less severe form of DR, non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NDR), affects both groups frequently:

■ 80 percent of Type 1 and 84 percent of Type 2 insulin-dependent diabetics after 15 years' duration of disease

■ 53 percent of Type 2 non-insulin-dependent diabetics after 19 years.

The second misconception about the two types of diabetes is that Type 2 is a disease of older people. An estimated 50 percent of cases occur in individuals less than 60 years of age, and children are becoming an increasingly important target group for the development of Type 2 diabetes. The dramatic increase in the prevalence of Type 2 diabetes has been tied to the rising epidemic of obesity in the U.S.

Childhood obesity is a special concern, being associated with high-calorie, fast food-based diets and the lack of exercise due to the growing preference of many children for video games and computers over sports and other physical activity.

| Learning Outcomes |

|---|

| At the conclusion of this Level II credit education course, participants should be able to: 1. Apply the principles of Healthy Sight Counseling (HSC). 2. Articulate the important relationship between ocular and systematic health. 3. Understand the basic aspects of diabetes and diabetic eye disease. 4. Better recommend spectacle lens enhancements for the diabetic patient. Test procedures: Following the article is a test consisting of 20 questions. To receive ABO continuing education credit, respondents must correctly answer at least 16 of the 20 test questions. This course has been approved by the Council on Optometric Practitioner Education for two hours of continuing education credit. If you pass this course, you will receive credit from the Irving Bennett Business and Practice Management Center at the Pennsylvania College of Optometry at Salus University. The COPE-ID number is #23121-GO. Use the attached form between pages 4 and 5 for your responses (you may photocopy the blank form for multiple respondents). Answer card forms must be received no later than April 30, 2009. Note: Some states do not accept home study courses for continuing education credit. Check with the licensing board in your state to see if this course qualifies.

Top: Mild non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR) or background diabetic retinopathy with microaneurysms and retinal hemorrhage Bottom: Moderate non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy with retinal hemorrhages, exudates, and diabetic macular edema (DME)

Top: Proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) with extensive retinal hemorrhages and neovascularization of the optic nervehead Bottom: Severe proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) with hemorrhages, exudates, neovascularization, fibrosis, and traction retinal detachment |

DIABETES: THE EYE DISEASE

The eye is one of the most important end organs for complications of diabetes. There are two types of ocular diabetic complications: direct and indirect.

Diabetic retinopathy is the primary direct complication of diabetes in the eye. There are two main categories of DR:

1. Non-proliferative

2. Proliferative

The Clinical Diabetic Retinopathy Disease Severity Scale subdivides non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR) into mild, moderate, and severe NPDR forms.

NPDR is caused by the development of microaneurysms in capillary walls. Its clinical manifestations include hemorrhages, microaneurysms, venous beading, hard exudates (often coalescing in the macula), and diabetic retinal edema (DRE). (See images above.)

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) is the most severe form of diabetic retinopathy, resulting from persistent and profound retinal ischemia, leading to neovascularization of the retina and the optic nervehead, retinal and vitreous hemorrhage, and retinal scarring and fibrosis ending in traction retinal detachment. (See images above.)

Cataract, AMD, and glaucoma: In addition to diabetic retinopathy, there are also some indirect ocular complications of diabetes. These include an increased incidence of several important vision-threatening ocular diseases that tend to occur with greater frequency in the diabetic patient. The most important are cataract, age-related macular degeneration, and glaucoma.

A number of epidemiological studies have demonstrated the increased frequency of cortical and posterior subcapsular cataracts in patients with diabetes.

In diabetics over age 65, there was a two-fold increase in the incidence of cataracts when compared to age-matched non-diabetic controls; this number increased to three- to four-fold in diabetics under age 65 compared to age-matched non-diabetics.

Elevated glycemic index (dGI) has been identified as a risk measure both for diabetes and for the severity of diabetes. Elevated dGI is also a risk factor for age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

Certain racial and socioeconomic groups at higher risk for the development of diabetes also show a higher incidence of glaucoma. The African-American population in the U.S. is a prime example of this medical double jeopardy.

ULTRAVIOLET RADIATION EXPOSURE

There is a convincing body of laboratory and epidemiological evidence linking ultraviolet radiation exposure to a number of ocular diseases—including cataract and age-related macular degeneration. There is additional evidence suggesting that the diabetic eye may be at a greater risk for such UVR-related ocular diseases. As far as cataractogenesis is concerned, select physiologic processes observed in UVR-related cataract development, including superoxide formation and lipid peroxidation, are also important in disease processes in the diabetic eye.

Diabetic retinopathy may increase the vulnerability of photoreceptors and retinal pigment epithelial cells to phototoxic damage. Retinal damage associated with chronic exposure to UVR and visible light may increase the vulnerability of retinal cells to various pathophysiologic mechanisms associated with diabetic retinopathy.

QUALITY OF VISION

In addition to decreasing the quantity of vision, through both its direct (DR) and its indirect (cataract and AMD) ocular complications, diabetes can also affect the quality of vision in diabetic patients. Wide swings in glycemic levels can produce troublesome shifts in refractive errors. (This is especially important in undiagnosed diabetics where otherwise unexplained fluctuations in refraction can suggest a diagnosis of diabetes.)

Some medications used to treat diabetes can also alter the refractive status and produce bothersome photosensitivity. When vision has already been compromised by disease, such quality of vision parameters as contrast sensitivity, glare, and color discrimination become more important in allowing the individual with less-than-normal visual acuity to maximize the visual experience and achieve the best visual comfort and convenience possible. Eyeglass lens enhancements such as fixed tint or photochromic lenses, anti-reflective (AR) coatings, and polarizing lenses are useful tools to help achieve these goals.

The best treatment for diabetes the eye disease is effective therapy for diabetes the systemic disease. The hallmark of diabetic management is glycemic control, and currently the preferred measures of adequate control are blood glucose levels (fasting blood sugars 70 to 130 mg/dL) and hemoglobin A1C (target range 6.5 to 7.0 percent). It has been estimated that the risk of developing diabetic retinopathy drops 21 percent and the risk of progression of such retinopathy decreases by 43 percent with every 1 percent decrease in hemoglobin A1C.

When diabetic retinopathy does occur, ophthalmic treatments include focal and pan-retinal photocoagulation, vitrectomy, membrane peeling, and retinal detachment repair. The Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network (DRCR), sponsored by the National Eye Institute (NEI), supports ongoing research efforts and clinical trials of potential new therapies for DR.

Of current interest are a number of recent therapies for AMD that are being investigated in cases of DR complicated by diabetic macular edema (DME). These include intravitreal injections of anti-VEGF factors and steroids.

Diabetes type 2 may be a preventable disease. As in all areas of medical practice, and in keeping with the principles of Healthy Sight Counseling, prevention remains the best medicine. Counseling on appropriate dietary and lifestyle modifications and educating patients on risk factors for diabetes and the need for regular eye check-ups can go a long way in avoiding the ocular complications of diabetes, or at least in minimizing these complications and maximizing Healthy Sight in the diabetic.